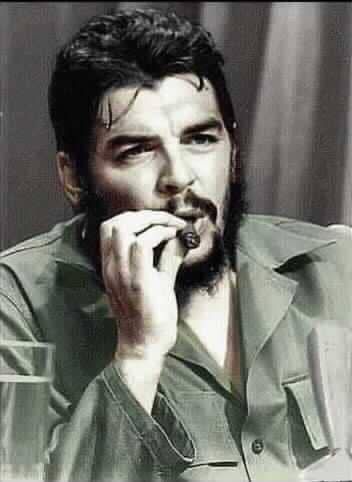

Ernesto Guevara de la Serna, popularly known as ‘Che,’ was born on June 14, 1928, in Argentina. A doctor by profession, he involved himself in revolutionary activities from his student days. He was with the political activists of Guatemala when the elected government of Jacobo Árbenz was overthrown by a CIA-backed coup in 1954. He escaped to Mexico, where he met the exiled Cuban revolutionaries led by Fidel Castro. He joined them in their struggle to liberate Cuba from the Batista regime.

“Che” was the name his Cuban compañeros gave him, a popular form of address in Argentina. He sailed with the Cuban revolutionaries on the famous yacht ‘Granma’ as a doctor, later being promoted to commander. Che played an important role in the success of the Cuban revolution, leading a guerilla column in the final battle. Finally, Batista fled the country on January 1, 1959.

Che became a key player in Fidel’s revolutionary government. First, he was appointed president of the Industrial Department, and later, he became the president of the National Bank of Cuba. He represented Cuba at various international forums, including the UN, and sought to build a grand alliance of developing nations against American supremacy. Expanding the influence of the Cuban revolution was his main aim, but he knew it couldn’t be achieved through diplomacy alone. Always believing in the words of José Martí, “The best form of saying is doing,” Che left Cuba to join the guerilla movement in Congo. He returned to Cuba in 1965 and then went to Bolivia to prepare for another revolution.

Che arrived in Bolivia in November 1966 and set up a small guerilla unit. The following is an entry from Che’s Bolivian Diary:

“Everything has gone quite well; my arrival was without incident; half the troops have arrived, also without incident, although they were somewhat delayed; Ricardo’s main collaborators are joining the struggle, come what may. The general outlook seems good in this remote region and everything indicates that we could be here for practically as long as necessary. The plans are: to wait for the rest of the troops, increase the number of Bolivians to at least 20, and then commence operations. We still need to see how Monje reacts and how Guevara’s people conduct themselves.”

They began attacks in March, achieving some early victories. But in the end, they were surrounded. “In the Bolivian campaign, Che acted with his proverbial tenacity, skill, stoicism, and exemplary attitude. It might be said that he was consumed by the importance of the mission he had assigned himself, and at all times he proceeded with a spirit of irreproachable responsibility,” said Fidel Castro. Castro also pointed out the decisive factor in Che’s defeat: “It was the ambush at La Higuera (on September 26, 1967) that created a situation they could not overcome.” In that ambush, the vanguard group was killed, and several others were wounded. Che and his men were intercepted when they were heading towards a peasant area in daylight. Che was fully aware of the risk of moving during the day, but he chose to do so to aid the team’s doctor, who was in very poor physical condition. Che was wounded and captured by U.S.-trained Bolivian counter-insurgency troops on October 8, 1967.

“October 9 – in that poor little schoolhouse in La Higuera, Che patiently waited for death. The order to kill him came from Washington; the underlings duly obeyed, and with one bullet after another, they stole the vigor from the guerilla fighter’s body.”

On August 20, 1960, addressing medical students, Che said, “I realized one fundamental thing: to be a revolutionary doctor, or to be a revolutionary, there must first be a revolution… A revolution needs what we have in Cuba: an entire people mobilized, who have learned the use of arms and the practice of combative unity, who know what a weapon is worth and what the people’s unity is worth.” Yet, he seems to have forgotten this when he went to Bolivia.

Today, October 9, marks the anniversary of Che’s death. His enemies may have succeeded in killing Che Guevara, but they failed miserably in erasing his memory. Che has become a global symbol of resistance. The ruthless nature of imperialism and its new tactics of colonialism have made it necessary to remember Che.

He is not only a symbol of resistance but also a symbol of revolutionary internationalism. As Che once said, “Every drop of blood spilled in a land under whose flag one was not born is experience gathered by the survivor to be applied later in the struggle for the liberation of one’s own country. And every people that liberates itself is a step in the battle for the liberation of one’s own people.” This encapsulates the spirit of his internationalism. But what is the state of internationalism now?

Today, imperialists send mercenaries everywhere to suppress popular movements, while terrorists spread across geographical boundaries. However, there is no sign of ‘Revolutionary Internationalism.’ Why has this happened? Despite Che’s belief in internationalism, he only fought in national liberation struggles. He considered the poor people of Bolivia his comrades, but they didn’t accept him. This wasn’t due to ignorance; it was their narrow nationalism. In Bolivia, Che was a foreigner. Mercenaries fight for alien regimes driven by money, and fundamentalists are motivated by religious indoctrination. Class consciousness has failed in the face of the power of money and religion—this is the tragedy of our times. What is the way out?

Globalization has erased the geographical boundaries of nation-states. Sovereignty has become a meaningless word. However, we can extract positive outcomes from this. Opposing globalization with nationalism is not the solution. Instead, we must build revolutionary internationalism, achieved through popular movements, not NGOs. Reinventing Che as a symbol of ‘Revolutionary Internationalism’ should be our foremost task.

(Published in Kafila.org on 09.10.2008)